I see regular questions about wave table oscillators in various forums. While the process is straight forward, I sympathize that it’s not so simple to figure out what’s important if you really want to understand how it works. For instance, the choice of table size and interpolation—how do these affect the oscillator quality? I’ll give an overview here, which I hope helps in thinking about wave table oscillators.

Generating a signal

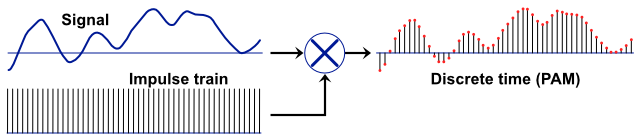

With a goal to generate a tone, we have an idea that instead of computing a tone for an arbitrary amount of time, we can save a lot of setup time and memory by computing just one cycle of the tone at initialization time, storing in a table, and playing it back repeatedly as needed.

This works perfectly and can play back any wave without aliasing. The problem is that the musical pitch will be related to the number of samples in the table and the sample rate. Even if we made a table for every possible pitch we intend to play, the tuning will be off for many intended notes, because we’re restricted to an integer number of samples.

Tuning the signal

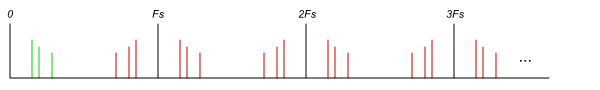

We can solve the tuning problem, and avoid building a lot of tables, by resampling a single-cycle wave table, the equivalent of slowing down or speeding up the wave. The problem with slowing down the wave is that waveforms with infinite harmonics, such as sawtooth, will have a increasingly noticeable drop in high end the more we pitch it down. The easy solution is to start with a table that’s long enough to fit all the harmonics we can hear, for the lowest note we need, and only change pitch in the upward direction. To pitch up, we use an increment greater than 1 as we step through the table. To get at all possibles pitches, we step by a non-integer increment—2.0 pitches the tone up and octave, 1.5 pitches up a fifth. Of course, this means we need to interpolate between samples in our wave table. How we do this is a major consideration in a wave table oscillator.

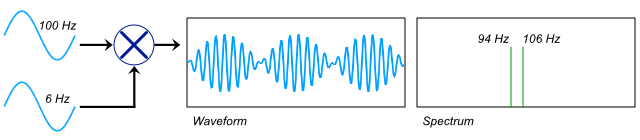

Aliasing

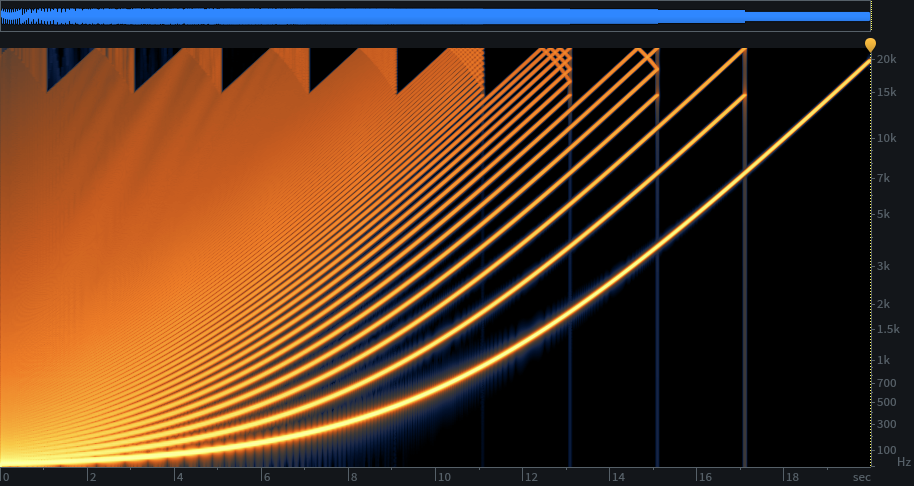

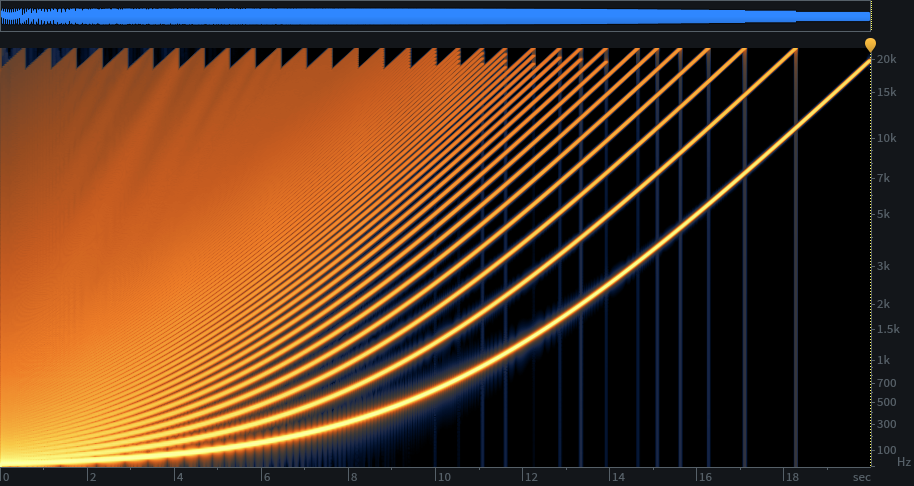

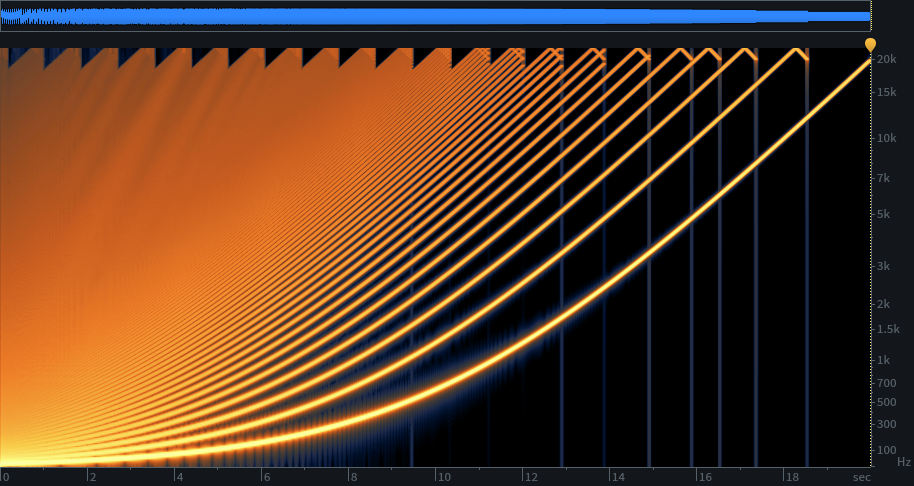

The problem with pitching in the upward direction is aliasing, as harmonics are rasied above half the sample rate. We could implement a nice lowpass filter to remove the offending harmonics before the interpolation. But a cheaper solution is to pre-compute filtered tables, and choose the appropriate table as needed, depending on the target pitch. This is why my wave table oscillator uses a collection of tables. Read the wave table oscillator series for the details, I won’t cover this aspect further here. Just understand that we need to remove harmonics before resampling, for precisely the same reason we use a lowpass filter before the analog-to-digital converter when sampling. The multi-table approach simply lets us do the filter beforehand to make the oscillator more efficient.

Choosing table size

As noted previously, table size is determined primarily by a combination of the lowest pitch needed and how many harmonics we need. For instance, we’d like our sawtooth wave to have all harmonics up to as high as we can hear (let’s say 20 kHz). For a pitch of 20 Hz, that means 1001 harmonics (20, 40, 60, 80…20000). The sampling theorem tells us we need something over two samples for the highest frequency component, so clearly we need a table size of at least 2003. For convenience, let’s make that 2048, a power of two.

Further, if we want to save memory for our tables that serve higher frequencies, we can cut the table size in half for each octave we move up. A table serving 40 Hz could be 1024 samples, 80 Hz, 512 samples, and so on.

The choice of interpolation method

If we have a very good interpolator—ideally a “sinc” interpolator—our job is done. But such interpolators are computational expensive, and we might want to run many oscillators at the same time. To reduce overhead per sample, we can can implement a cheaper interpolator. Choices include no interpolation, such as just grabbing the nearest table value, linear interpolation, which estimates the sample with a straight line between the two adjacent samples when the index falls between them, and more complex interpolation that requires three or more table points. Cutting to the chase, we’d like to use linear, if we can. It produces significantly better results than no interpolation, but has only a small amount of additional computation per sample.

But by giving up on the idea of using an ideal interpolator, we introduce error. Linear interpolation works extremely well for heavily oversample signals. Recall that using a 512 sample sine table with linear interpolation, the results a good as we have any chance of hearing—error is -97 db relative to the signal. Sine waves are smooth, and as we have more samples per cycle, the curve between samples approaches a straight line, and linear interpolation approaches perfection.

The catch is that our table of 2048 for 20 Hz doesn’t necessarily hold a sine wave. For a sawtooth, it holds harmonic 1001 with just over two samples. Linear interpolation fails miserably for producing that harmonic. The errors cause significant distortion and aliasing with that harmonic. And a whole lot of harmonics below it, but improving as we move towards the lower harmonics where they will be awesome.

Our first thought might be that we need a table size 128 times as large, to get up above 512 for the highest harmonic. So, 262,144 samples, just for the lowest table?

No, we cheat

Here’s where psychoacoustics saves the day. Even though our distortion and noise floor figures for the higher harmonics look pretty grim, it’s extremely difficult to hear the problem over the sweetly rendered lower harmonics. And, fortunately, oscillators we like to listen to won’t likely have a weak fundamental and a strong extremely-high harmonic with nothing in between. Natural and pleasant sounding tones are heavily biased to the lower harmonics.

Also, if we choose to keep constant table sizes, then as we move up each octave, removing higher harmonics, the tables are progressively more oversampled as a result. Constant table sizes are convenient anyway, and don’t impact storage significantly. So, at the low end we’re saved by masking, and though we lose masking as we move up in frequency, at the same time the linear interpolation improves with increasingly oversampled tables. At the highest note we intend to play, near 20 kHz, error will be something like -140 dB relative to the signal.